Manual – Open Data for Students

January 5, 2018

Tool – Smart Analysis of Government Data

February 1, 2018Improving the Sharing and Use of Air Pollution Data for Advocacy and Awareness

This blog was written by the D4D Program team and is also published on the Open Nepal website.

Outdoor air pollution has become a matter of grave concern in Nepal. Anthropogenic emissions from various sources such as industry, vehicles, people’s homes, and road construction have increased manifold and have led to many environmental and health problems. Nepal has growing levels of PM2.5, which is considered one of the most harmful air pollutants as it lodges into human lungs and blood tissues thereby increasing the chances of lung cancer and other respiratory diseases. Recently, the Environment Performance Index (EPI)ranked Nepal the worst among 180 countries in terms of air quality, and the Pollution Index 2018 ranked Kathmandu as the 5th most polluted city in the world. Strong, coordinated and effective efforts are needed to tackle the growing problem of air pollution in Nepal, and civil society has an important role to play in advocating for these efforts.

A precondition for any evidence-based advocacy is data and information. Data presents the evidence required for informed advocacy aimed at improving current practices, policies and plans. With good quality open data on air pollution, effective advocacy and greater awareness can be built on how air pollution affects us, and effective policies and tools can be developed to reduce air pollution.

Considering the importance of evidence based advocacy on the issue of air pollution, the Data for Development in Nepal program last month brought together a range of experts and advocates in the field of air pollution in a workshop to discuss challenges and identify opportunities around the production, sharing and use of data for air pollution advocacy and awareness. This blog highlights key insights emerging from the workshop.

Production of air quality data: Air pollution data for Nepal does exist, but its reliability and limited coverage means it is not always useful for advocacy and awareness raising.

Nepal has a number of air quality monitoring stations – thirteen installed by ICIMOD, Department of Environment, and US State Department (seven stations in Kathmandu, three in Pokhara, and one each in Lumbini, Langtang, and Dhulikhel), ten sensors installed by Dristhi in Kathmandu, and also several used for academic and one-off studies. However, the need for more stations with greater geographical coverage resonated during the workshop, particularly during the Terai region due to the air pollution from industry and trans-border air flow. One particular area of concern is that the different actors producing air quality data (including ICIMOD, Dristhi, LEADERs, Department of the Environment etc.) use different kinds of sensors, which can prevent comparative analysis and the determination of trends. It was also felt that the data currently produced is not sufficiently detailed to enable advanced modelling to understand the environmental impact of difference sources of emission, predictions on the way pollutants will behave in the atmosphere, or to test different theories on risk. This kind of multifaceted measurements would provide important inputs to government and other concerned stakeholders for mitigation measures and to inform policy change. Another challenge raised during the workshop was the high cost of robust air quality sensors and their installation. Although data collected by affordable sensors are also reliable, the longevity and geographical coverage of those sensors are also an issue. The idea was discussed of disclosing the geographical location of the sensors in a map alongside details of the sensor type to support data users to better understand the limitations of the data they are using.

Sharing of air quality data: The sharing of open data on air pollution is vital for the issue to be effectively challenged.

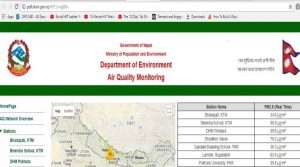

Government data is considered as the most valid and authentic data source by many actors. Workshop participants shared how the validity of air quality data and interpretation produced by civil society is often queried when the data is not produced by the government. A key concern for these groups is the government’s reluctance to fully open up their air quality data. Real-time air quality measurements are publicly shown on the Department of Environment website, both in tables and as graphs, for each of the government run air quality stations. However, the value of this data is limited as historic data is not shown which prevents the use of this data for determining past trends and predictive analysis. In addition, the data is shared only as text and graphs on the website, rather than being published in a format that enables data download for analysis and re-use of data. The workshop participants felt that government air quality data could be more effectively shared as open data in order to accommodate the wide array of users and uses of the data – for example, similar to that made available on the OpenAQ website. For this to happen, issues of financial resourcing and technical expertise within government to open up the data need to be addressed, as well as potentially cultural issues that prevent data sharing.

Use of air quality data: The use of data can improve and strengthen civil society’s advocacy efforts and conversely civil society can play an important role in making the data meaningful for people.

Participants agreed that it is important to encourage the government to take essential steps to reduce air pollution. Although various policies have been developed in Nepal, they have not been materialized in practice. It was felt by many in the room that creative and constructive campaigns could be developed to raise public awareness (for example a successful campaign called Maskmandu was recently conducted by CAAN where activists put masks on public statues and laid on the street- this grabbed the attention from government, media, and public). Participants raised that air quality data could play an important role in such campaigns, for example helping to encourage certain behaviors when the data indicates air quality is poor. Civil society can play an important role in making air quality data meaningful to people, as numbers in a table can be very difficult for the average person to understand. The effective and meaningful communication of air quality data is vital if it is to make impact. One example shared by workshop participants was that of a Mexican website sharing air quality analysis in a child-friendly manner, to advice children and their parents when it is safe to play outside. The idea of an easily-understandable air pollution index interpreting reliable data to advise citizens on air quality levels was raised as an important initiative for Nepal.

With air pollution an ever-growing concern in Nepal, the developments in the production, sharing and use of data need to keep pace so that the issue can be effectively addressed. It is necessary to create a solid data infrastructure that can produce valid and reliable data that has a good geographic coverage and enables effective modelling of flows. This data then needs to be openly available (as open data) to those who want to use it. When this is the case, advocacy and awareness campaigns can become more evidence-based so that citizens are made aware of the dangers of air pollution and government is made aware of air pollution-related policy needs.